Wuhan University

Wuhan University

Sep 2024 – Jun 2025

Genetic code expansion (GCE) enables site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids but is limited by truncated protein accumulation from competition with host release factors. We developed a eukaryotic expression system that distinguishes and removes truncations using protein circuit design. Incorporating an N-terminal degron, a C-terminal localization tag, and a split TEV protease, the system selectively degraded truncated proteins while preserving full-length ones. This approach improved yields 1.4-fold and reduced truncations 4.6-fold, with tunability via small molecules and alternative localization signals. By enhancing protein fidelity and yield, our strategy strengthens the utility of GCE for precise protein engineering and live-cell imaging.

Synthetic biology and protein engineering increasingly demand precise regulation of protein structure and function in living cells. Genetic code expansion (GCE) provides a powerful strategy by enabling site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids through engineered aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pairs, facilitating protein remodeling and fluorescent labeling.

However, competition between GCE’s orthogonal translation components and host release factors frequently causes premature termination, leading to truncated proteins and reduced yields of full-length products. This inefficiency has limited the broader utility of GCE in protein engineering and live-cell applications.

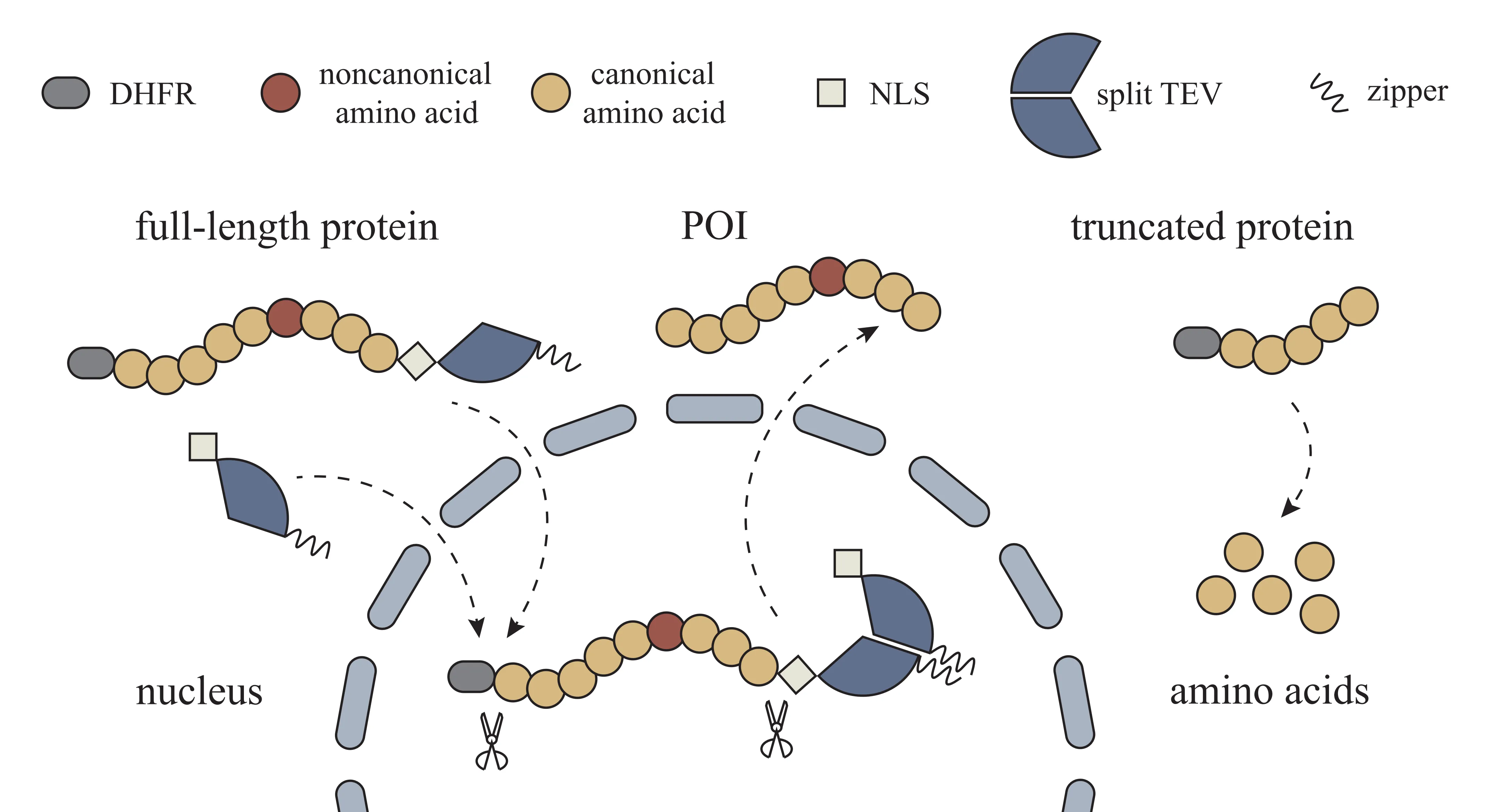

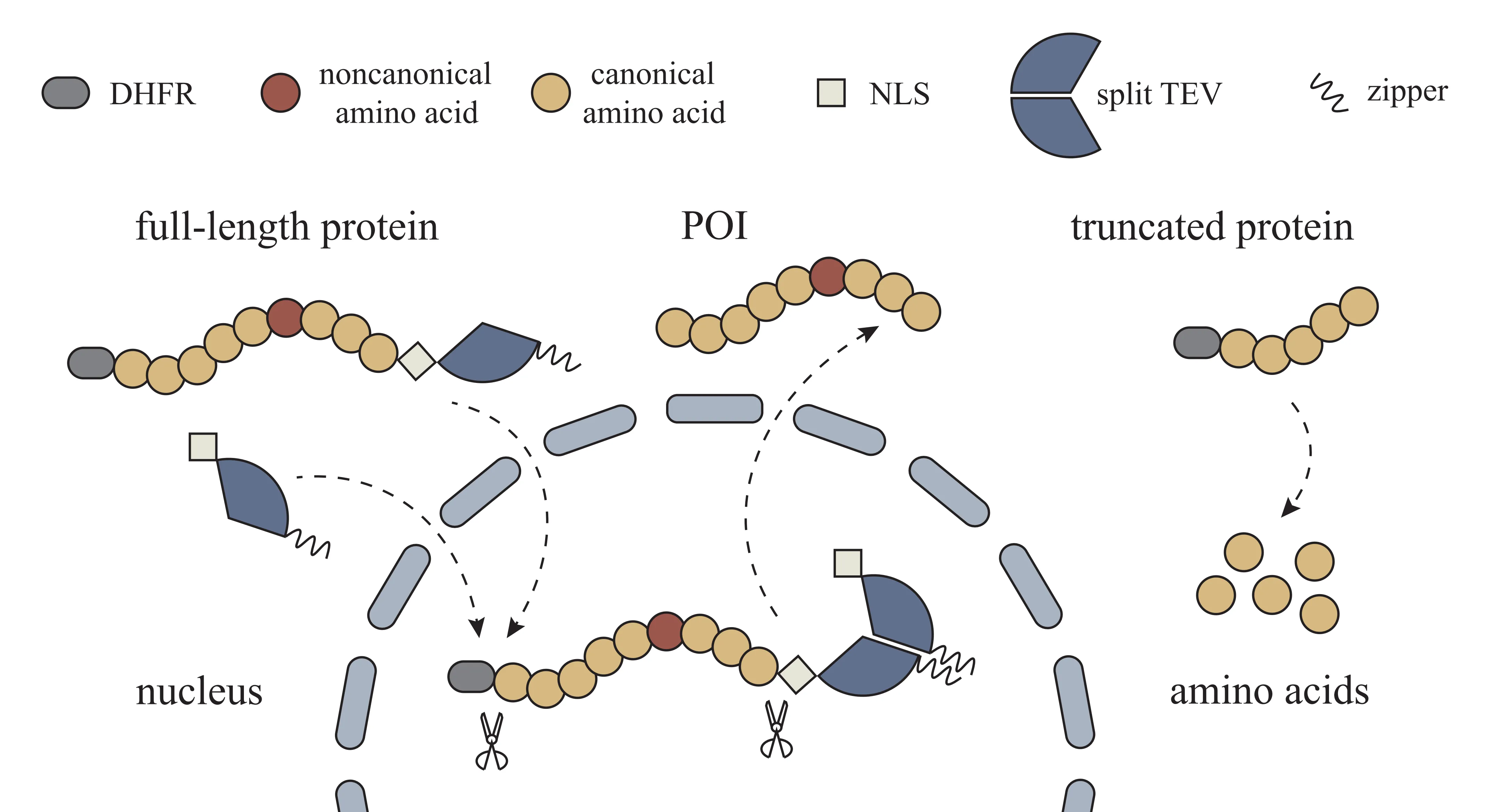

To address this challenge, we developed a eukaryotic expression system that selectively eliminates truncated proteins while preserving complete products. The design integrates an N-terminal degron (DHFR), a C-terminal localization tag, and a reconfigurable split TEV protease, enabling spatial separation and targeted degradation of truncations.

This approach improved protein fidelity, increasing full-length yields and markedly reducing truncations, with further tunability through small-molecule drugs and alternative localization signals. By enhancing the efficiency of GCE, our system expands its applicability in synthetic biology, particularly for protein engineering and live-cell imaging.

To construct the degradation-based circuit, we designed protein sequences containing a degron at the N-terminus, a TEV protease cleavage site, and a localization signal at the C-terminus. For the nuclear localization system, two plasmids were generated:

The degron (mutated E. coli DHFR) promotes ubiquitin-mediated degradation in mammalian cells. The nuclear localization signal (NLS) directs the protein into the nucleus via the importin α pathway. The Czipper/Nzipper leucine zipper sequences mediate dimerization and thereby reconstitute the split TEV protease, enabling site-specific cleavage (Fig. 1).

To obtain eukaryotic expression plasmids (pNLS-C and pNLS-N), individual fragments were amplified by PCR with homologous arms and assembled into linearized vectors using Gibson recombination. Constructs were verified by sequencing. Endotoxin-free plasmids were prepared for mammalian cell transfection.

To monitor amber suppression efficiency, an iRFP-EGFP fusion reporter was constructed with a TAG mutation at EGFP position 39. In the absence of readthrough, truncated proteins contain only iRFP and emit far-red fluorescence. Successful readthrough produces full-length iRFP-EGFP, which emits both far-red and green fluorescence.

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with pNLS-C, pNLS-N, and the amber suppression system plasmid pcDNA3.1 U6FulltRNA-NES-PylRS(AF) (pPylRS-tRNA). Noncanonical amino acid (BOC) was supplemented as required. For time-controlled degradation experiments, 1 μM Trimethoprim (TMP) was added during medium replacement at 4–6 h post-transfection and removed at defined time intervals before cell collection.

Fluorescence imaging was performed at 24 h post-transfection using live HEK293T cells. Proteins were extracted by RIPA lysis and analyzed by immunoblotting to detect cleavage fragments and quantify the ratio of full-length to truncated proteins.

In conventional GCE systems, the amber stop codon (TAG) is reassigned to encode a noncanonical amino acid (ncAA). However, because TAG remains recognized by release factors, premature termination generates truncated proteins lacking C-terminal regions. To selectively eliminate these truncation products, we engineered a circuit in which (i) a degron was fused to the N-terminus, (ii) a localization signal and a protease cleavage site were fused to the C-terminus, and (iii) a split TEV protease was expressed in cells with the same localization pattern as the full-length protein.

In this design, full-length proteins are first recognized and cleaved by TEV, thereby removing the degron and localization sequences and restoring proper subcellular localization. In contrast, truncated proteins, lacking the C-terminal localization signal and protease site, remain degron-tagged and undergo proteasomal degradation (Fig. 1).

The iRFP-EGFP reporter system was used to monitor amber suppression efficiency. In cases of readthrough failure, cells displayed only far-red fluorescence. Successful ncAA incorporation produced dual fluorescence signals (far-red and green), allowing direct visualization of readthrough efficiency.

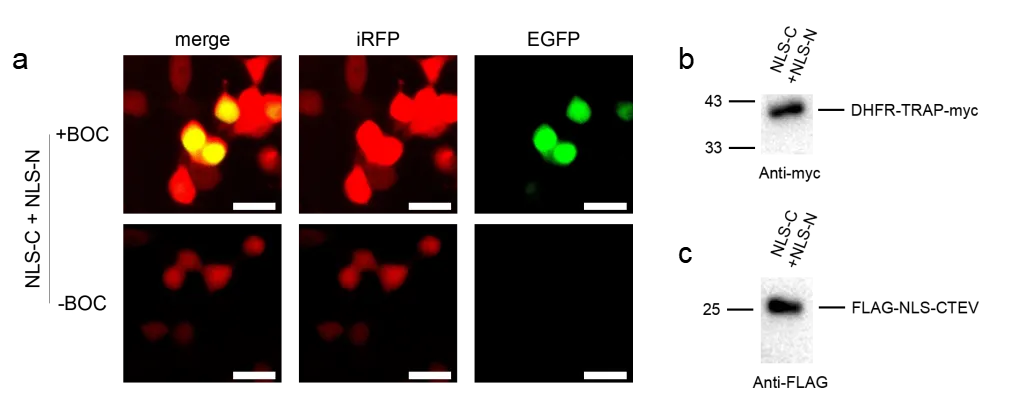

To validate the design, HEK293T cells were transfected with pNLS-C, pNLS-N, and pPylRS-tRNA in the presence of ncAA. Live-cell imaging revealed widespread red fluorescence throughout the cytoplasm, while green fluorescence was primarily nuclear, consistent with nuclear localization of the full-length product (Fig. 2a).

Immunoblotting further demonstrated successful TEV-mediated cleavage. The expected cleavage fragments were observed: an N-terminal DHFR-TRAP-myc fragment and a C-terminal Flag-NLS-CTEV fragment (Fig. 2b,c). These results confirm that split TEV protease activity is reconstituted when its two halves are colocalized, enabling specific processing of the engineered substrates.

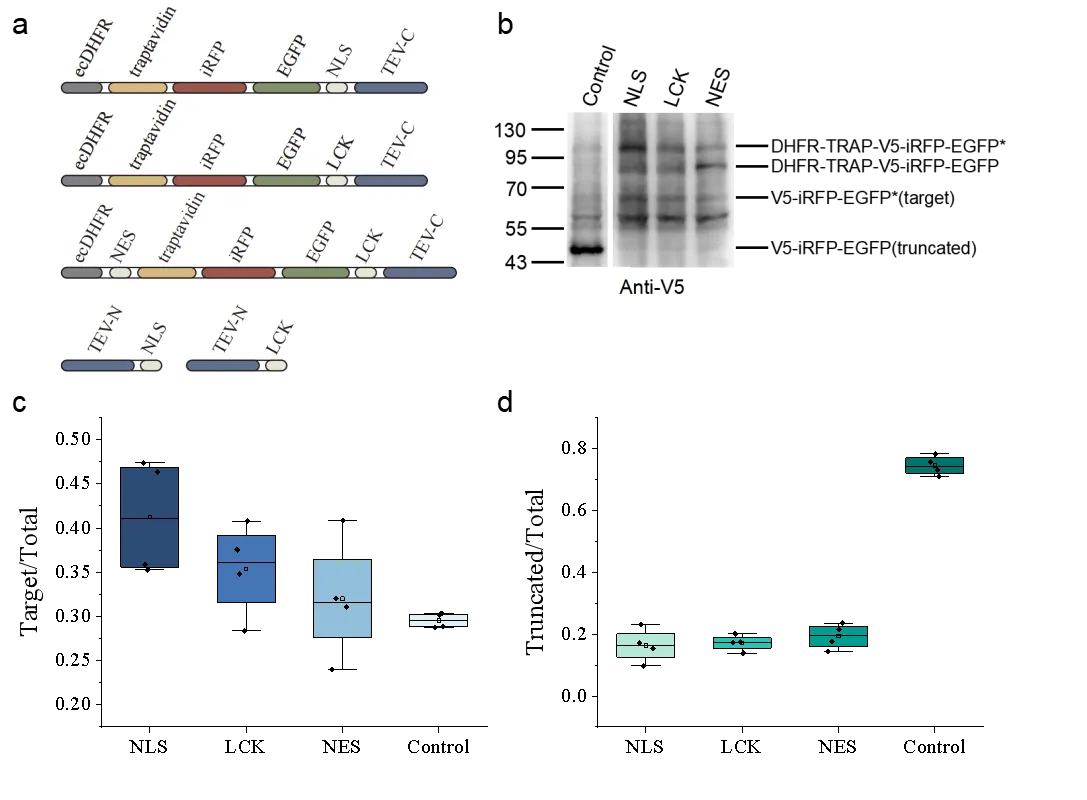

To assess the generalizability of the truncation-elimination system, constructs with different localization signals were designed:

A control reporter plasmid (pcDNA3.1 v5-iRFP-EGFP(39TAG)) was used to establish baseline GCE efficiency.

Immunoblotting and quantitative analysis revealed that the NLS-based system was most effective. Compared with the control, the proportion of full-length proteins increased from ~29% to ~41-fold (1.4× increase), while truncated products decreased from ~74% to ~16% (4.6× reduction) (Fig. 3b–d). These findings indicate that localization signals can be tailored to optimize degradation of truncated proteins in different cellular contexts.

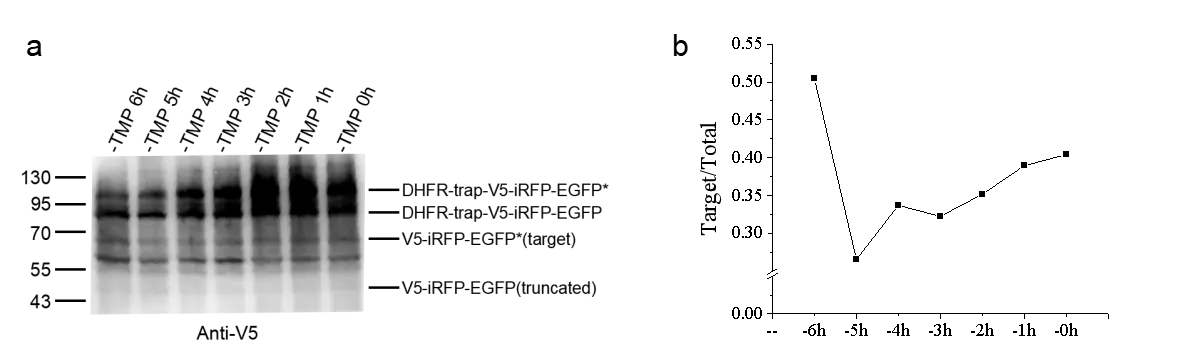

During initial testing, some full-length proteins underwent degradation before protease cleavage, reducing system efficiency. To overcome this, we applied TMP, which binds to the degron (mutated DHFR) and blocks its recognition by E3 ligases, thereby temporarily preventing degradation.

When TMP was added after transfection and removed at defined time points before sampling, we observed a time-dependent effect. The optimal improvement was achieved when TMP was removed 6 h before collection, allowing sufficient protease cleavage prior to degron-mediated degradation (Fig. 4b). This strategy of temporally separating cleavage and degradation significantly enhanced elimination of truncation products.